A glyphosate update for this early week in April 2025. Some quick bullet points:

We are now ten years out for the monograph 112 meeting in 2015,

No substaintial changes in regulatory opinions regarding the carcinogenicity of glyphosate,

The most recent verdict in Barnes v Monsanto at ~$2.65B should alarm Bayer – and I have a lot more to say on this and media coverage.

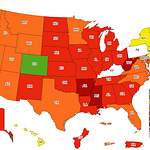

State-by-State legislation efforts continue and are universally reported as an attempt to shield from liability. This is not the whole truth, but I do believe these efforts are a tactical mistake. Promoting uniformity in safety labeling does represent a strong argument in the sphere of preemption.

Federal efforts to clarify Congressional Intent by amending FIFRA and term ‘misbranding’ is a positive step that has gone unnoticed by proponents and activists.

Similar preemption language exists in the Agriculture Improvement Act that now will remain in effect until the end of 2025 although the House Committee on Agriculture has announced plans for a new Farm Bill before Memorial Day.

Historic - is a 3rd petition to the Supreme Court of a glyphosate case. This follows the 3rd circuit ruling in Schaffner v. Monsanto.1 The circuit split with the 9th and 11th circuits being important, but a Supreme Court hearing is far from certain.

So here, someone had asked what I thought of the petition, and so I’ll spend some time here to summarize the 51 pages, both good and bad.

Question Presented

First, what is The Question being Presented to the Supreme Court:

Whether FIFRA preempts a state-law failure-to-warn claim where EPA has repeatedly concluded that the warning is not required, and the warning cannot be added to a product without EPA approval.

This question touches on two central legal issues that Monsanto/Bayer continues to face in court. First, the matter of causation—specifically, whether glyphosate was a substantial factor in causing non-Hodgkins lymphoma (NHL) in plaintiffs. Second, the question of failure to warn—whether Monsanto/Bayer knew or should have known about the potential risks of glyphosate exposure and failed to adequately inform users, making the harm foreseeable. The legal landscape is a little more complex, but these two points form the backbone of litigation.

Beyond the ‘Question Presented’ section, the ‘Parties to the Proceeding’ are notable. This case may be referred to as Monsanto v Durnell. It appears Bayer’s legal representatives see this case as the springboard to being granted a hearing with some pretty good reasoning — following appeal denials out of the State of Missouri.2

In the Durnell case, the jury found Monsanto not liable on all claims except for failure-to-warn, for which the company was held liable and awarded Durnell $1.25 million in damages. Monsanto subsequently moved for judgment notwithstanding the verdict, arguing that the failure-to-warn claim was preempted by FIFRA. That motion was denied and additional appeals were denied. However, this standalone failure-to-warn verdict, along with the court’s rejection of Monsanto’s preemption argument, is directly relevant, fit-for-purpose, and instructive for the court to review. That is the short summary of the petition in a nutshell. But… let me give you details about the …

The good and bad

One sentence goes to the heart of the question and is the overarching theme and isdrawn together in the end is that the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (“FIFRA”) includes a “[u]niformity” provision that expressly preempts all state “requirements for labeling or packaging” that are “in addition to or different from those required under” FIFRA. 7 U.S.C. §136v(b). It’s all simply - a uniformity argument.

But, despite starting strong, the brief quickly takes a turn that feels both off-putting and confusing:

“More than 100,000 cases have been filed seeking to hold Monsanto liable based on a supposed link to cancer that the EPA has exhaustively studied and rejected as unfounded.”

While this sets a stage, isn’t this a bit whiny. Worse, it invites the predictable rebuttal that “registration is not a shield from liability” — a line of argument you can expect to hear repeatedly as this unfolds.

Good for Bayer—and in a very clever move, the company points to the previous brief of the Solicitor General - Elizabeth Prelogar. For those unfamiliar here—Prelogar, as representing the position of the United States—was remarkable, but not in a flattering sense. She advised the Court to deny the Hardeman petition arguing that “the preemption question does not warrant review” and also cited “a change in administration” as a meaningful factor. That rationale raised questions from those on Capitol Hill and prompted action from Congressional staff. Whether a shift in administration should influence how science and legal questions are handled remains an open—and let’s say troubling—question.3

So the brief nails the previous SG here -here’s the quote-

“This Court previously recognized the importance of the question presented when it called for the views of the Solicitor General … In response, the United States recommended that this Court not “grant review unless and until a conflict in authority emerges.”4 That conflict has now emerged. There is no reason for further delay. Boom…

There is an even deeper dive here that I will footnote regarding Daubert standards in the previous writ regarding expert testimony, but that deserves far more space.5

Notable Quips

Good for Bayer: The “label is the law” citing the EPA Pesticide Registration Manual 3 as updated April 2017 that emphasizes changes to labeling may proceed only by formal amendment. Pretty good.

IARC’s classification reflected a hazard assessment, meaning a theoretical determination of carcinogenic potential; it did not assess the actual risk posed under real-world conditions. Of course, this could have been much better and I and others I have cooresponded with have mentioned this on numerous occasions. Also, I do think it is important to distinguish IARC from the monograph program.

“No shortage of national and international health organizations that rejected IARC’s position, including the European Union’s European Chemicals Agency (ECHA), its European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), and the national health authorities of Australia, Canada, Germany, and New Zealand.” Of course, these are foreign, non-domestic organizations. Perhaps they should not be admissible in a US courtroom – but then, should that also apply to the monograph program that serves as the foundation for these torts.

Not great: Citing the California case ‘National Association of Wheat Growers v. Bonta.’6 This legal action was filed originally against Director Ziese of Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment (OEHHA) & California Attorney General Becerra—a case rooted in an entirely different legal arena: compelled commercial speech. Still, it’s worth noting and appreciating the 2020 Shubb decision as later upheld by the Ninth Circuit. That opinion is well worth a read—packed with zingers aimed squarely at the OEHHA.7 – a whole other story.

Weak: Citing the Goodis “Dear Registrant” letter. This has always puzzled me, as it carries no force of law and merely reflects the EPA administration’s disagreement with monograph at that time. It serves primarily to show that EPA considered all submitted data. This being THE most important distinction behind the divergence of opinion and consensus with other world regulatory authorities — which, in all honesty, aren’t comparable to the monograph in the first place. Again, read the Shubb opinion to better understand - it’s only 34 pages and really ‘reasonable’.

Ordinary consumers do not interpret warnings in accordance with a complex web of statutes, regulations, and court decisions, and the most obvious reading of the Proposition 65 cancer warning is that exposure to glyphosate in fact causes cancer. A reasonable consumer may understand that if the warning says “known to cause cancer,” there could be a small minority of studies or experts disputing whether the substance in fact causes cancer. However, a reasonable consumer would not understand that a substance is “known to cause cancer” where only one health organization had found that the substance in question causes cancer and virtually all other government agencies and health organization that have reviewed studies on the chemical had found there was no evidence that it caused cancer. Under these facts, the message that glyphosate is known to cause cancer is misleading at best. (Docket no 97 at 14, emphias to not added)

I would add that few truly understand the numerous differences that exist between regulatory agencies and the monograph program, and I didn’t like the absolute here of ‘no evidence’ as zero evidence is not unlike zero risk that often does not exist for many things.

In the category of truly bad: The brief blatantly misrepresents Judge Friedland’s Ninth Circuit Court opinion8—the very ruling that led EPA to withdraw its 2020 interim health decision. EPA should have been better represented at that hearing and formulated a better response. The addition of Cathryn Britton’s memorandum was a meaningful step in the right direction.9 However, if this case moves forward to a hearing, good luck defending this section of the brief.

Acknowledgment of an EPA “implementation mistake” warranted far more than a footnote—especially when considering the continued approval of glyphosate products and formulations without cancer warnings. The pivot to complaining that plaintiffs’ lawyers have spent an estimated $131 million on more than 600,000 TV ads feels wildly misplaced. I like ATRA, but citing the American Tort Reform Association (ATRA) in this context only undercuts the argument and makes this more like a grievance than any legal reasoning. In the section…

Reasons for Granting Petition

Pretty good on misbranding. Splits of authority do not get any clearer than that currently existing between the 3rd, 9th, and 11th circuits. I’m not sure if good or bad, but noting that the 3rd circuit rejected the 9th and 11th circuits’ “force of law” analyses with a proclamation that a force of law analyses generally have no place when interpreting an express preemption provision? – I just don’t know how that fits into the legal landscape.

The section on ‘the decision below is wrong’ is confusing but hits hard with common language. When a state tort claim requires a pesticide manufacturer to add a warning that EPA has repeatedly concluded is not only unnecessary, but also “false and misleading,”— FIFRA preempts that claim. Any other rule would undermine the nationwide “[u]niformity” in pesticide labeling that Congress set out to achieve. In simple terms “State law says “Add this warning” --- federal law says “Don’t” – A very good section for Bayer legal — but— quickly undone in a following section following a sophisticated legal argument section that I’ll footnote.10

About 30 pages in, just awful and that which will be undoubtedly be disputed and receive response -- reads as follows:

“Even if FIFRA did not expressly bar Monsanto from adding a cancer warning on its own, EPA would unquestionably reject any attempt to add a cancer warning to Roundup”

OK, I’ve read the opinions of the 9th and 11th circuits and that is no easy task with the 11th circuit and the ping-ponging & en blac review in Carson v Monsanto. I do wonder if the authors here read these opinions, and while I can understand the desire to further promote the ‘impossibility of possibilities of impossibilities”, this fails. Open to be challenged, that EPA would ‘unquestionably reject’ is just not supported. This section only becomes more compounded with footnote 7 and again references to letters that have no force-of-law.

Closing: “The Crazy-Quilt”

A very good start to closing and why this is so important.

This issue and circuit split over EPA-labeling extends beyond glyphosate. Absolutely, well done, let’s hear more. In fact, this issue could extend beyond our borders. The decisions here are important to the statutory goal of ensuring uniformity that builds trust. It presents the unacceptable alternative to restoring the pre-1972 status quo that Congress sought to replace. FIFRA amendments were intended to address the chaos and confusion engendered by the dozens of disparate state pesticide-labeling regimes.11

Through examples, the brief then extends this concept to other federal statutes involving medical devices12, the Poultry Products Inspection Act13 , Federal Meat Inspection Act14 , and those regarding National Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act.15 It essentially asks, should each state have its own safety standards?

This echoes something I wrote about recently: the 2016 TSCA reform could have been cited here as it includes federal preemption language — being more appropriate in the EPA legal space. Additionally, it’s worth considering this through the lens of the Commerce Clause, especially when it comes to labels and placards used in chemical transportation. Should the safety or hazard labeling of a chemical change just because it crosses a state line? And what about international efforts to harmonize hazard classifications and pictograms? Should each city, county, state, or country design its own biohazard or radiological warning symbols? Product safety shouldn’t depend on politics or geography, a hazard is a hazard—no matter where it’s shipped, stored, or spilled.

To close - it is this idea of harmony and uniformity that is such an important topic — I’m going to sound like a broken record again - this extends to the creation of trust. Again, such an important topic…so I checked my potential bias below.16

Such an important topic — but sadly — Bayer closes the brief with a whimper – that trials are scheduled to occur in 2025 and 2026, and there is no reason for delay and every reason for this Court to grant review” - For me, the Bob Uecker catchphrase applies here – “just a little outside”

Stay safe…

REFERENCES

Schaffner v. Monsanto Corp.,113 F.4th 364, 370-71 (3d Cir. 2024)

The last being dated on the 1st of April this year. [references: Durnell v. Monsanto Co., No. SC100975 (Mo.) (application for transfer denied Apr. 1, 2025). Durnell v. Monsanto Co., No. ED 112410 (Mo. Ct. App.) (opinion and judgment issued Feb. 11, 2025). Durnell v. Monsanto Co., No. 1922-CC00221 (Mo. Cir. Ct. of the City of St. Louis) (judgment entered Jun. 24, 2024]

(1) House Oversight; (2) Agriculture - Associated - LINK & LINK

U.S. Br.19, Monsanto Co. v. Hardeman, No. 21-241 (U.S. filed May 10, 2022). That conflict has now emerged. There is no reason for further delay. The Court should grant this petition and resolve that conflict. Associated links

Going really deep & sorry as this is one key aspect of the brief that I believe received little attention, was the court’s explicit rejection of claims that a more permissive legal standard had been applied upon appeal. Appellate courts found that the district courts had properly applied the Daubert standard and did not abuse discretion in admitting expert testimony – and that experts relied on robust scientific evidence, adhered to sound methodology, and appropriately ruled out idiopathic causation – I can’t disagree more. Docket & Brief

National Association of Wheat Growers v. Bonta, 85 F.4th 1263, 1270 (9th Cir. 2023)

NRDC v USEPA - 06/17/22

Memorandum from Cathryn Britton, Branch Chief, Risk Management and Implementation Branch V, Pesticide Reevaluation Division, to Glyphosate Registration Review Docket (EPA-HQOPP-2009-0361) (Sept. 21, 2022) - LINK

Page 28/51 delves into a very sophisticated legal argument as to ‘prima facie evidence’ that a pesticides labeling complies with the registration provisions, really needs a post of it’s own. Then closes with how lack of uniformity would lead to the “very proliferation of divergent state and federal labeling requirements Congress sought to end. Respondent’s failure-to-warn claim is doubly preempted because it is “impossible” for Monsanto “to comply with both state and federal requirements.” Mut. Pharm. Co. v. Bartlett, 570 U.S. 472, 480 (2013).

Bates, 544 U.S. at 452 n.26.

21 U.S.C §360k(a)

PPIA, §467e

FMIA, §678

49 U.S.C. §30103(b)

Footnote: summary provided by Google NotebookLM (checking for bias) Glyphosate Litigation: FIFRA Preemption and Supreme Court Review - An analysis of the ongoing legal battles surrounding glyphosate, specifically focusing on a petition to the Supreme Court in April 2025. The central legal question revolves around whether federal pesticide labeling regulations preempt state failure-to-warn claims, especially when the EPA has deemed the warning unnecessary. The author examines arguments for and against granting the petition, highlighting inconsistencies and strategic missteps within Bayer's brief, alongside potentially strong points concerning the need for national uniformity in labeling. The analysis also touches on the broader implications of this case for other federally regulated industries where uniformity is a key principle.

In summary, improvements to Bayer's legal strategy, as reflected in the analysis of their Supreme Court petition, would likely involve sharpening the focus on core legal arguments, avoiding weaker or misrepresentative points, adopting a more neutral and legally reasoned tone, and ensuring key arguments are thoroughly and persuasively presented.

REVIEW

A reasonably accurate and insightful commentary on the potential strengths and weaknesses of the arguments presented in Bayer/Monsanto's petition for a writ of certiorari to the Supreme Court, as reflected in the Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Missouri Court of Appeals (Monsanto Company v John L Durnell). It correctly identifies the central legal arguments related to FIFRA preemption and uniformity, while also pointing out instances where the brief might rely on less persuasive points or adopt a tone that could be counterproductive. Our previous conversation also touched upon the need for Bayer to refine their legal strategy, which aligns with the critical analysis provided

Share this post