A recent lawsuit targeting Girl Scout Cookies has grabbed headlines, raising concerns about contaminants. This post, will take on some of the responses by some science communicators that may not be popular.

I understand that this is more than just legal pressure. While seeking legal remedies like damages and injunctions against deceptive practices is part of this lawsuit, it is clear these are two purposes: legal pressure and media amplification. The timing, language, and media attention surrounding this case makes it "hard not to conclude that one of the primary goals here was to generate public visibility". In essence, these are "instruments of narrative control—designed to sustain engagement through fear, uncertainty, and doubt." — this strategy being effective with audiences already distrustful of modern life, including the food we eat and institutions intrusted with food safety. What does not help, is when scientific communicators add to uncertainties by misrepresenting toxicology. First…

Is this another "Food Babe" moment?

Well, yes, targeting consumer brands with safety claims is a standard approach used by groups like Moms Across America and figures like Zen Honeycutt. The legal complaint here leans heavily on an article from GMOScience, co-authored by individuals known for mixing fringe science with sweeping health claims.1

This can be contrasted slightly with the tort industry, where law firms often start by looking for the deepest corporate pockets—targeting companies not necessarily to change behavior, but to secure big settlements, rather than seeing the lawsuit as part of a broader campaign for engagement and change.

Some details of this lawsuit — it is a class action filed in the Eastern District of New York naming the Girl Scouts of the USA, Ferrero U.S.A., Inc., and Interbake Foods, LLC (ABC Bakers) as defendants. The named plaintiff, Amy Mayo, alleges that Girl Scout Cookies are misleadingly marketed as cookies that are wholesome and safe, especially for children, despite containing glyphosate, lead, and cadmium found by independent laboratory testing. I’ll provide a link to the actually filing as post by WKRN News - LINK & will also footnote more legal details of the filing below.2

The Challenging Science of Contaminants

Now, taking on some of the scientific communicators here — might not be popular. First recognize that food babe approach works because of the nature of the contaminants themselves, in particular, heavy metals like lead, mercury, arsenic, and cadmium. Do not add to uncertainties…

Your First communication — when heavy metals are involved — needs to be an acknolwedgement that there are no benefits to exposure. None.

This is why influencers can successfully lean into the "no safe level" narrative – because, in this specific context, they are not wrong to do so. Expect to keep seeing headlines about heavy metals in food and baby formula, especially when it comes to risks for children and during pregnancy. As analytical methods get more sensitive, we’re able to detect even smaller amounts of these toxicants. If you haven’t noticed, this has been going on for decades. But when we layer in scientific jargon, the conversation around heavy metal risks often gets muddled.

Beyond "How Many Cookies Can I Eat?"

A common and problematic tactic in food risk debates is the misuse of benchmarks like Maximum Residue Limits (MRLs), Acceptable Daily Intakes (ADIs), No Observed Adverse Effect Levels (NOAELs), or Action Levels—or worse, relying on crude proxies like "cookie consumption estimates." While these regulatory thresholds serve important functions in specific contexts, they have nuanced definitions and they are not interchangeable.

Unfortunately, their complexity makes them easy targets for misrepresentation. What’s especially troubling is how some science communicators, including those presented as experts, have failed to understand the differences—sometimes producing risk estimates that span over 10,000-fold, like from 73 to 73,0004 cookies.

Such discrepancies don’t clarify risk; they erode public trust, fail to relate scientific nuance into confusion, and reduce food safety expertise to the level of guesswork. When inconsistencies are this extreme, it's not just a communication failure—it can become a tool to disparage science itself.

ALARA: The Guiding Principle

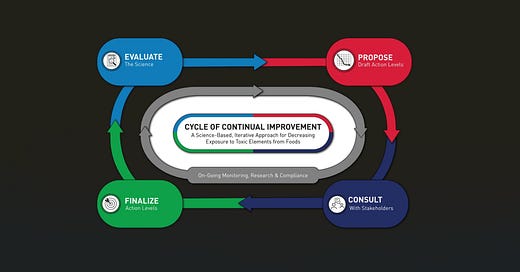

The crucial principle that is too often missing from these discussions is ALARA—As Low As Reasonably Achievable.

ALARA is foundational when dealing with heavy metal contaminants, especially when protecting vulnerable populations like children. It’s not just about whether something meets a legal limit; it's about doing everything possible to minimize exposure, even if levels are below a regulatory threshold or action level.

This principle is actively being pursued by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) through its Closer to Zero Initiative, launched in April 2021. The clear goal is to reduce dietary exposures to environmental contaminants like heavy metals as much as possible without sacrificing access to nutritious food. It’s a serious public health effort. You can learn more about it at the link provided. https://www.fda.gov/food/environmental-contaminants-food/closer-zero-reducing-childhood-exposure-contaminants-foods.

That said, it's important to remember that heavy metals like lead, arsenic, cadmium, and mercury are naturally occurring and ubiquitous in the environment. They've always been present. So, while Closer to Zero is commendable and necessary, achieving "zero exposure" may be impossible — yet, aiming for ALARA is the correct direction.

The Media's Role

With heavy metals, I’ll have more to say in a future post about the irony of influencer-endorsed, non-GMO pink salts—some of which are contaminated with the same heavy metals and promoted by the very same individuals seeking engagement. Not in a fear sense, but salts “untouched by human hand”, "natural" and "clean."

But what is perhaps most concerning in these situations is how readily mainstream media outlets seize upon stories that promote fear, uncertainty, and doubt—often prioritizing engagement over scientific nuance. I understand, but perhaps others need to better understand that the coverage frequently reflects the profit-driven news cycle, by authors of little scientific acumen, favoring alarmism over accuracy, amplifying fears over the actual risks, and knee-jerk virality over reflection, due diligence, and research from those with an understanding of toxicology.5

What Happens Next?

Bringing this back to the cookie case. Legally, I’d think a settlement is likely. The plaintiff is seeking various remedies, including monetary damages, restitution, and an injunction to prevent future deceptive marketing. I don’t think you’ll see a jury trial or that this will proceed very far. This might not make it to a courtroom, but that remains to be seen. Again,

For Science Communicators

This case is a stark reminder. Relying on simplistic cookie counts or misunderstood toxicological benchmarks weakens important messages. I won’t go further into dose-response relationships or how some of the inaccuracies of how ‘the dose makes the poison’ can be misused and misunderstood here. But, when communicating about contaminants, especially heavy metals, we must do better:

Understand and articulate the principle of ALARA.

Highlight relevant public health efforts like the FDA's Closer to Zero Initiative.

Acknowledge the complexities and that metals are naturally occuring in the environment and food grown in soil, both conventionally or organically will acquire these metals.6

Do - critique the lack of expertise and potentially misleading tactics used by those reporting risk.

To close, this isn't just about one lawsuit or one cookie. It's about how we talk about contaminants, protect vulnerable populations, and resist narratives driven by fear and doubt rather than sound science and public health principles. The toxicology of heavy metals is somewhat unique in many perspectives that occupies chapters in toxicological textbooks with some very rich history. With that…stay smart — informed — and…

Stay safe out there…

P.S. I asked ChatGPT to summarize this article - cute…

Footnote & References

Danger in Dough - https://gmoscience.org/2024/12/27/danger-in-the-dough/

At the heart of the lawsuit is the allegation that Girl Scout Cookies are marketed as wholesome and safe, particularly for children—a population afforded special protections under the Food Quality Protection Act (FQPA) of 1996 due to their heightened vulnerability to environmental contaminants. The plaintiff asserts that independent laboratory analyses conducted in late 2024 identified the presence of several substances of concern, including glyphosate, lead, and cadmium, thereby undermining the safety assurances conveyed to consumers.

Mayo argues that the defendants violated state-level consumer protection laws and were unjustly enriched by not disclosing these toxicants. The result, she claims, is that consumers either overpaid for a product they believed was safe or wouldn’t have bought the cookies at all had they known.

The suit seeks a wide range of remedies, including damages, restitution, and an injunction to prevent further deceptive practices. It covers all Girl Scout Cookie purchasers in the U.S., and specifically names a New York subclass.

Legally, I had to search a bit, but this falls under New York’s General Business Law—specifically:

§ 349, which addresses deceptive business practices, and

§ 350, which covers false and misleading advertising related to product safety.

Mayo, representing both herself and the proposed class, is asking the court to certify the class under Rule 23 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. She’s seeking not just financial damages but also equitable relief—like requiring the defendants to notify potential class members and to stop the deceptive practices going forward. That includes things like injunctive relief, restitution, and disgorgement of profits gained through the alleged misconduct. The suit also requests attorney’s fees, interest before and after judgment, and, notably, a trial by jury.

WebMD - "Looking at the Peanut Butter Patties' lead level, a child would have to eat close to seven cookies in a day to exceed the FDA reference value for dietary intake of lead. Most children don't eat seven or more cookies per day," said Katarzyna Kordas, PhD, an associate professor of epidemiology and environmental health at the University at Buffalo School of Public Health. She studies the effects of heavy metals on human health, especially children's health. https://www.webmd.com/diet/news/20250325/girl-scout-cookies-heavy-metals-and-whats-safe-to-eat

Toxicologist Joe Zagorski from Michigan State University, speaking to NPR this month, dismissed the study’s alarmist tone, noting a 70-pound child would need to consume 73,000 Thin Mints daily to reach a harmful glyphosate level. [based on glyphosate, not heavy metals, but wouldn’t you consider lead, mercury, arsenic, and cadmium first and foremost? - and yes, I recognize that glyphosate is there for engagement] https://www.foodsafetynews.com/2025/04/girl-scout-cookies-face-scrutiny-over-safety-and-sustainability-concerns/

I’ll point to an old Society of Toxicology Survey here - really believe that this needs to be repeated given the >15years that have past: “SOT members think are doing a terrible job reporting toxicological risks.” Are Chemicals Killing Us? https://reason.com/2009/05/21/are-chemicals-killing-us/

Testing Results for Arsenic, Lead, Cadmium and Mercury https://www.fda.gov/food/environmental-contaminants-food/testing-results-arsenic-lead-cadmium-and-mercury

Share this post