I know this is pretty specialized content for a niche audience, but since I drafted this about two weeks ago, I thought I’d go ahead and finish it and share a few thoughts after taking a closer look at Barnes v. Monsanto that recently ended with a $2.65 billion dollar verdict.

This case originally started as Barnes v. Home Depot before being restructured during pre-trial proceedings. For those interested in source material, much of the trial coverage is available through Courtroom View Network (LINK).1

This will be somewhat detailed, but if you want to distill the essence of these kinds of tort cases into two words, they would be harms and duties. The alleged harm in this case is cancer causation; the core duty is the duty to warn.

TORT OVERVIEW and LITIGATION

In chemical or product liability litigation, establishing liability hinges on demonstrating causation—both general and specific. General causation addresses whether a product or chemical can cause the alleged harm in a population at large, while specific causation links the exposure to the individual plaintiff's injury.

The concept of a "substantial factor" is central to proving harm. It requires showing that the exposure played a meaningful role in causing the injury, even if it wasn't the sole cause. It need not be the only contributing factor, but it must be significant enough that the harm likely would not have occurred without it. Closely related is the legal “but-for” test:

But for the defendant’s conduct, would the harm have occurred?

Now let’s shift to duty, the duty to warn—an issue deeply rooted in toxicology, risk assessment, and risk communication. When a duty to warn exists — is one of the best of questions to ask’ an often provocative and contested question where California warnings are great examples to explore.

Manufacturers and employers are obligated to warn of known or reasonably foreseeable risks. A failure to provide adequate warnings may constitute negligence. Foreseeable risks are those that a prudent and reasonable individual or entity should anticipate as a potential consequence of their actions. In tort law, foreseeability helps define the scope of a duty of care and, ultimately, liability.

Of course, this can cut both ways: one might argue that a reasonable person should understand inherent risks in handling chemicals. Yet in litigation, plaintiffs often argue that the risks were obscure, minimized, or actively misrepresented.

It’s also important to note that negligence alone isn’t sufficient. The plaintiff must establish that proper warnings would have altered their behavior in a way that would have prevented the harm. If any element—causation, duty to warn, or negligence—is not adequately demonstrated, the case may not prevail.

The Barnes Case

In Barnes v. Monsanto, the plaintiff, John Barnes, alleged that his decades-long use of Monsanto’s herbicide Roundup on his residential property led to his development of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Although his cancer is currently in remission, he requires ongoing maintenance chemotherapy.

Barnes contended not only that his exposure to glyphosate was a substantial factor in causing his illness, but also that Monsanto failed to adequately warn of the product’s potential carcinogenic risks and had knowledge of those dangers aforethought. In essence, the case centered on both harm (cancer causation) and duty (failure to warn).

The jury ultimately sides with the plaintiff — the verdict was substantial: $65 million in compensatory damages and $2 billion in punitive damages—bringing the total award to $2.65 billion. To put this in context, the Pilliod case, another high-profile Roundup trial, initially resulted in $1 billion in punitive damages for the two plaintiffs, Alva and Alberta Pilliod, plus roughly $55 million in compensatory damages. That award was later reduced to $86.7 million.

Monsanto, now a subsidiary of Bayer, maintained throughout the trial that there is no scientifically valid link between glyphosate and cancer. As paraphrased from courtroom coverage, the company argued that Mr. Barnes’s use of Roundup was intermittent over the years and that the scientific evidence does not support a causal connection between glyphosate exposure and non-Hodgkin lymphoma.2

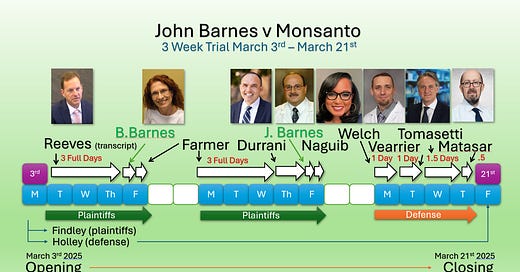

Trial Flow - Disclosure

So I’m going to talk a little bit about the trial flow and in writing here, I felt a need to disclose and will footnote that as turning to the trial timeline.3 Regarding the testimony, I can’t provide granular details, which would require access, significant time, and resources. While those details are certainly important, the intent here is more to highlight key differences between Barnes and the earlier bellwether trials —and why those differences should raise serious concerns for Bayer.

The original bellwether cases—Johnson, Hardeman, and Pilliod—provides content and sets the stage for later trials. The Pilliod trial in returning a verdict of over $2 billion dollars was the turning point that caused Bayer to pursue a global settlement strategy, ultimately exceeding $10 billion.

There has been ongoing public commentary questioning Bayer’s decision to settle, often framed as an admission of guilt or liability. But consider the situation from the vantage point of Bayer’s leadership in 2019. At that point, the company had lost three consecutive trials—including one (Pilliod) in which the trial structure had been carefully crafted to Bayer’s advantage ending in a mulit-billion dollar verdict. At that time, an estimated 40,000 additional claims are pending—that number is growing—and risk modeling becomes very sobering. If even 1% of those cases yielded a similarly high verdict, potential liability could stretch into hundreds of billions of dollars. In that light, settling was not an admission of wrongdoing—it was a strategic imperative to contain unpredictable legal exposure.

Fast forward to today and the Barnes trial. While the legal landscape has evolved, Barnes introduces new dynamics, new expert testimony, and courtroom strategies that diverge from the earliest trials. These differences pose renewed risks for Bayer, suggesting the litigation challenges are far from over.

Let’s examine what makes Barnes distinct.

Plaintiffs’ Case

So, who were the expert witnesses for the plaintiffs in Barnes? Familiar names from prior trials—Christopher Portier, Charles Benbrook, William Sawyer, Dennis Weisenburger, Beatrice Ritz, and Charles Jameson—do not appear here.

Instead, and quite notably, the plaintiffs open their case with testimony from two individuals closely associated with Monsanto — Toxicologists Dr. William Reeves and Dr. Donna Farmer. This strategic choice is both unusual and significant.

The trial used selected excerpts from the deposition of Dr. Reeves who was a Bayer Crop Science’s Global Health and Safety Issues Management Lead. Dr. Reeves holds a Ph.D. in toxicology and has been a central figure in Monsanto’s defense in previous litigation.4 The transcript used is likely from a deposition that was conducted in 2019 by attorney Brent Wisner and spanned more than three hours being recorded about seven weeks prior to the Pilliod trial.

Starting with Monsanto’s own toxicologists—rather than independent experts that were at times successfully targeted by defense attorneys—marks a deliberate pivot in courtroom strategy and reflects a new approach by the plaintiffs to frame the company’s internal knowledge and risk communication practices as central to their case.

Following three days of transcript readings and rebuttal presented, the plaintiffs called Dr. Donna Farmer, live, to testify in person where her testimony spans approximately three and a half days.

Dr. Farmer is arguably the most knowledgeable toxicologist on glyphosate, with decades of experience at Monsanto. She joined the company in 1991 and held several roles within regulatory affairs that make her a central figure in both internal risk assessments and public communications around glyphosate safety. I’ll include a link to one prior deposition5 and public appearances from the early days of the litigation.

Plaintiffs then use Dr. Timur Durrani6 – a clinical Professor of Medicine and Pharmacy at the UCSF. Board certified in Occupational Medicine, Family Medicine, Preventive Medicine, and Medical Toxicology. He has functioned as a medical toxicology consultant for the ATSDR and EPA region 9. Dr. Durrani's analysis is primarily based on epidemiology studies by McDuffie, Eriksson, and Pahwa that has been previously criticized as failing to adjust for use of other pesticides — not unlike the Zhang publication, last year characterized as junk science by Judge Chhabria.7

Beverly Barnes (spouse) then briefly testifies – followed by local oncologist Dr. Hosam Naguib MD.8 Plaintiff, John Barnes testifies at the end of two weeks to wrap presentations.

Defense Case

The defense presents its case during the third and final week of the trial, calling four expert witnesses.

First was Dr. Connie Welch-DuJardin9 who brings over 27 years of experience in environmental law and regulatory compliance. She holds a B.S. in Chemistry from Virginia State University and a doctorate — not in a scientific field. Nonetheless, her background supports her qualifications as an expert in pesticide regulation. She spent 17 years within the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Office of Pesticide Programs (OPP), ultimately serving as a Branch Chief in the Antimicrobials Division, where she was responsible for implementing key aspects of the Food Quality Protection Act (FQPA).

Next was Dr. David Vearrier, M.D., M.P.H10 — who offered brief testimony. Dr. Vearrier is board-certified in occupational medicine, addiction medicine, medical toxicology, and emergency medicine. He holds degrees from UC Berkeley and obtained his medical degree from UC San Diego in 2000. Notably, he has served as Chair of Occupational and Environmental Toxicology within the American Academy of Clinical Toxicology (AACT), lending strong credentials to his evaluation of glyphosate exposure and associated risks.

The defense then calls Dr. Cristian Tomasetti11 described by some as a “star witness” in prior proceedings, for two days of testimony. Dr. Tomasetti is internationally recognized for his work on cancer etiology and tumor evolution, particularly in shifting paradigms around cancer’s stochastic elements. He currently serves as Director of the Center for Cancer Prevention, Early Detection, and Monitoring at City of Hope, and also leads the Division of Mathematics for Cancer Evolution and Early Detection within the Beckman Research Institute. Additionally, he is Professor and Director of Integrated Cancer Genomics at the Translational Genomics Research Institute (TGen).

Dr. Tomasetti’s testimony has not gone unchallenged in prior litigation. For context, see Pretrial Order No. 289 in the federal MDL that addresses objections to his expert opinions and his assertion that over 90–95% of lymphomas are idiopathic—claims that have become focal points in debates over causation thresholds and probabilistic modeling in toxic torts.12

The defense concluded its case with testimony from Dr. Matthew Matasar13, Chief of Blood Disorders at Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey and a recognized expert in the clinical management of lymphomas. Notably, in the Durnell trial, Dr. Matasar’s analysis aligns closely with the themes advanced by Dr. Tomasetti—particularly around the multifactorial and often idiopathic nature of lymphomas—reinforcing the defense’s argument that causation in individual cases remains highly uncertain.

Bayer - Concern

So, lots of experts here, highly qualified, and how did this work out, how did the defense team perform? The March 21st decision marked the fourth consecutive Roundup-related victory for Kyle Findley’s legal team, which appears to have developed a reliable trial strategy capable of securing substantial damage awards. In this case, the jury awarded $2 billion in punitive damages, signaling that jurors were responding strongly to Monsanto's conduct over the years. Some other firms will notice.14

According to press releases and a Courtroom View Network (CVN) interview, Monsanto intends to appeal the decision, arguing that it contradicts the weight of scientific evidence. The company remains committed to defending its products in court, noting that it has achieved favorable outcomes in 17 of the last 25 trials. Monsanto asserts, “Our track record demonstrates that we win when plaintiffs’ attorneys and their experts are not allowed to misrepresent the worldwide regulatory and scientific assessments that continue to support the products' safety.”

Significance

The magnitude of this verdict should not be understated. It represents one of the largest glyphosate-related awards to date. The firms representing the plaintiffs—Arnold & Itkin LLP and Kline & Specter PC—have demonstrated a winning formula, and with as many as 67,000 cases still pending, the potential for future outcomes looms large.

Key takeaways from this trial include:

The size of the verdict;

The relative speed with which the in-person portion of the trial progressed, but do know this was a 4-year process from the initial filing;

The notable absence of key experts from past trials, the defense team's reliance on a reduced roster, and use of Monsanto own toxicologists.

The absence of prominent past expert witnesses should raise significant concern for Bayer. This was the defense's 'A-team,' yet it culminated in a notable loss. A thorough analysis is warranted. Plaintiffs' counsel, instead of presenting a comprehensive lineup of causation experts, strategically called upon Monsanto's own toxicologists as witnesses. This approach reflects a significant shift in the litigation landscape—where carefully curated deposition transcripts can effectively shape a narrative of willful misconduct spanning decades. The strategy is straightforward: portray Monsanto as deliberately failing to warn the public, manipulating scientific publications and review, and prioritizing profits — or sales over safety. Expert scientific testimony may not be critical, nor the adjudication of the carcinogenic risks that are accepted widely across the global scientific regulatory community.15

To reiterate, full disclosure: I haven’t had the opportunity to review the full three weeks of trial testimony, but I am certainly tempted to dial up the Courtroom View Network subscription. But I don’t work for Bayer or legal firms, and hope others with more at stake might take that plunge and share more insights. One question I’ve raised several times is why Bayer doesn’t consider providing its own commentary on trial testimony. In the early rounds of litigation, much of the testimony presented by plaintiffs and defense was poor, biased, to the point of the word I always used carefully - that being ‘fraud’. But I’ve seen testimony that:

Compared glyphosate to chemical warfare agent sarin;

The registration of glyphosate was linked to the IBT scandal and associated controversies. Ironically, this very scandal became a catalyst for the development of Good Laboratory Practice (GLP) guidelines.

That ‘magic tumors’ might exist to the extent that pre-trials motions bar it’s use, but it might be equally magical that kidney tumors disappeared not to be seen again in multiple rodent bioassays.

Defense once claimed in reviewing genetic toxicology data that mutations might not cause cancer — when the somatic mutation theory remains the prevailing scientific model supported by extensive evidence.16

The notion that regulatory bodies like the EPA and EFSA ‘have blood on their hands’ & share responsibility for public health failures;

And, of course, a favorite infamous reference by toxicologist William Sawyer in the $2B dollar Pilliod trial — “you would look like a twisted hot dog” - I’d note that phosphoylation may not be a characteristic of phosphonates and there is good reason nobody talks about it.17

Close

In conclusion, the trial verdicts in the Roundup/glyphosate litigation have epitomized arbitrariness—unpredictable, inconsistent, that are indicative of a deeply flawed and untrustworthy legal process.

By definition, a process that lacks consistency and reliability is inherently untrustworthy. From my perspective, the outcomes of these trials are often shaped less by objective truth and more by pre-trial in limine motions18 , judicial discretion over evidentiary admissibility, courtroom theatrics, and strategic legal maneuvering. Others have observed that the personalities involved and the emotional dynamics exert a substantial influence on the final verdict.

These verdicts have been wildly inconsistent—at times unanimous, yet in completely opposing directions—driven more by procedural nuances, jury composition, and legal technicalities than by the strength or coherence of the underlying scientific evidence. Over the past several years, the same core case has been retried under varying circumstances and locations, often producing entirely divergent outcomes. For Bayer, this has meant enduring a legal environment where outcomes increasingly resemble a coin flip—introducing profound uncertainty for the company and undermining confidence in the judicial process itself. Such variability underscores the inherent unpredictability of the system and calls into question its reliability as a mechanism for adjudicating complex scientific matters. Financially, this may not be sustainable for Bayer or other target of the tort industry.

As such, I find myself in agreement with those advocating for tort reform. While I once believed that the conclave system, used in Australian litigation, might offer a path forward—particularly in the context of concurrent expert testimony—even that approach seems to have fallen short; the adversarial nature of litigation remains entrenched, and transparency continues to be an issue.19

In the end, these proceedings have shown us that the system, as it stands, leaves much to be desired in terms of objectivity and trustworthiness.

With that I’ll close20 - stay safe out there…

REFERENCES

CVN URL for video coverage (with subscription)

Plaintiffs are represented by Roy Barnes and John Bevis of the Barnes Law Group; Kyle Findley and Noah Wexler, of Arnold & Itkin; and Frank Bayuk, Bradley Pratt, and Christopher Lambden, of Bayuk Pratt. The defense is represented by William Holley II, and R. Thomas Warburton, of Bradley Arant Boult Cummings; John Kalas, of Nelson Mullins Riley & Scarborough; and Robert Ingram, of Moore Ingram Johnson & Steele. This trial was held in Cobb County State Court, before Judge Jane Manning. The actual trial lasted three weeks, starting Monday, March 3rd, ending Friday, March 21st. CVN did stream and record the trial (link above footnote 1). Judge Jane P. Manning was presiding - and note she has published some interesting and related legal articles.

While I initially intended to provide a comprehensive analysis of trial testimony, limitations of time and cost made that unfeasible. Those who know me understand that I follow litigation and scientific developments closely, within the limits of my patience and personal resources. I do not subscribe to paid legal services and rely primarily on open-source materials. That said, I did travel to San Bernardino to attend one day of closing arguments in the Stephens case—I felt compelled to witness it firsthand. I sat quietly in the back row of a small courtroom, behind a cluster of young attorneys and just behind the plaintiff and defense tables, where Donna Farmer was seated.

I have no conflicts of interest. I am not affiliated with Monsanto or Bayer, though individuals with such affiliations may follow me on social media. I am retired, but retain specialized knowledge and experience in toxicology through formal education, training, and practice. Broadly, I align with the positions of global regulatory agencies regarding glyphosate’s carcinogenicity, though not without some exceptions. I also have some personal and professional connections that shape my perspective:

I know a toxicologist who participated in IARC’s Monograph 112.

Another colleague—an alumnus of my graduate program—produced what I believe is the most incisive critique of the “key characteristics of carcinogens.”

I first encountered Dr. Cristian Tomasetti, a defense expert in this case, at a 2015 Genomic Medicine conference where he presented early findings.

As a graduate student, I had the opportunity to see Bruce Ames present, whose work challenged prevailing views on natural vs. synthetic chemicals. It took time, but I eventually came to fully appreciate the depth of his critiques of risk assessment paradigms.

Lastly, I wince at the phrase “the dose makes the poison,” given its frequent misattribution and oversimplification of toxicological principles.

William Reeves, was Global Health and Safety Issues Management Lead at Bayer Crop Science - Ph.D. in toxicology, a former Environmental Scientist with the California Environmental Protection Agency and has worked for a private consulting firms conducting risk assessments. I believe he is no longer with Monsanto/Bayer (LINK).

Donna Farmer- Deposition in 2019.

Appeal - Commonwealth Court of Pennsylvania - Ernest Caranci v. Monsanto Co. - Decided May 22, 2024 (case text link) 993 EDA 2024 2213 - 05-22-2024 ERNEST CARANCI and CARMELA CARANCI, Plaintiffs, v. MONSANTO COMPANY, et al., Defendants. Abbe F. Fletman, J.

Defendant Monsanto Company ("Monsanto") appeals this Court's orders of September 22, 2023, denying (in part) its motion to exclude the testimony of Timur Durrani, M.D. under Frye v. United States, 293 F. 1013 (D.C. Cir. \923) (followed in Grady v. Frito-Lay, Inc., 839 A.2d 1038 (Pa. 2003)) and denying its motion for summary judgment on failure-to-warn claims due to federal preemption. This Court adopts by reference the February 27, 2024, Opinion of the Honorable James Crumlish, III, on the issue of federal preemption. Opinion, Trial Court Docket ("Dkt.") at 2/27/24. Accordingly, this opinion focuses on the motion to exclude Dr. Durrani's testimony.

Because this Court neither abused its discretion in denying in part the motion to exclude Dr. Durrani nor erred in concluding that the failure-to-warn claims are not preempted, this Court respectfully requests the Superior Court affirm the orders of September 22, 2023

Dr. Durrani’s Expertise

In and appeal of Caranci v Monsanto, Dr. Durrani's analyses were criticized as being based on McDuffie, Eriksson, and Pahwa studies that failed to adjust for use of other pesticides. Monsanto asked the Court to assume the role of the expert and make scientific judgments on the significance of the limitations presented by scientific studies. The court believes that such scientific judgments fall within the scope of Dr. Durrani's expertise and are properly addressed by contrary expert testimony and cross examination.

Indeed, Monsanto presented expert reports from industrial hygienists Joshua Schaeffer, Ph.D. and Matthew Call criticizing Dr. Durrani's analysis and highlighting these concerns. (Motion to Exclude Durrani at Exs. C, D.) It is not this Court's role under Frye to resolve a dispute between scientists where both positions find support in scientific literature and result from an established and generally accepted methodology. Monsanto's argument that Dr. Durrani should have been precluded under Frye for failure to quantify the actual "dose" of glyphosate that Mr. Caranci experienced is inapposite, out of place, not fit, in this context. – Image that the argument where dose and frequency of dosing doesn’t matter in the mind of these judges?

To borrow from asbestos cases - which involve similar aerial exposures to a toxic product over many years with a latent injury arising years or decades after the first exposure - Pennsylvania courts have repeatedly rejected a quantification requirement because it would impose "an impossible burden of proof on plaintiffs”. See Rost v. Ford Motor Co., 151 A.3d 1032, 1052 (Pa. 2016)

(rejecting requirement of quantification in asbestos cases where there "is substantial doubt whether such quantification is possible" as doing so would "have the effect of creating an impossible burden of proof," and leaving comparison of multiple asbestos products to jury); Andaloro v. Armstrong World Industries, Inc.,199 A.2d 71, 86 (Pa. Super. 2002)(rejecting argument that plaintiff must quantify number of asbestos fibers attributable to a given defendant); Junge v. Garlocklnc, 629 A.2d 1027, 1029 (Pa. Super. 1993)(noting that Pennsylvania imposes "no requirement" on an asbestos plaintiff to "prove through an industrial hygienist, or any other kind of opinion witness, how many asbestos fibers are contained in the dust emissions from" a specific product). The Court finds this rationale persuasive in the current context.

This matter *12 involves allegations of latent injuries allegedly caused by aerial exposure to Roundup and that arise only after years or decades of regularly spraying Roundup. To require plaintiffs to specify their precise dosage would similarly impose an impossible burden of proof Finally, Monsanto's argument that Dr. Durrani failed to adequately address other risk factors for NHL (age, obesity, sex, ethnicity, "natural cell replication errors," and exposure to benzene) is unavailing. Statement of Errors at 1 6. Dr. Durrani considered age, sex, body weight, ethnicity, family history, exposure to benzene and other chemicals, radiation exposure, weakened immune system, autoimmune diseases, and relevant infections. Durrani Report at 55-56.

That Dr. Durrani did not reach the same conclusion as Monsanto's experts merely speaks to the weight of his testimony, not its admissibility under Frye. See Walsh v. BASF Corp., 191 A.3d 838, 845 (Pa. Super. 2018)(noting that differing conclusions and absence of treatise on point speak to weight of expert testimony, not admissibility), off d sub nom. Walsh Est. of Walsh v. BASF Corp., 234 A.3d 446 (Pa. 2020). Accordingly, this Court did not abuse its discretion in denying Monsanto's motion to exclude Dr. Durrani under Frye.

Pretrial Order 289 — and one Deposition

Given the scale of the Barnes verdict, it’s no surprise that the plaintiffs’ firm, Wisner Baum, would take a keen interest. While the specifics of how these materials are shared or leveraged across firms in ongoing litigation are not publicly clear, it's reasonable to assume that other legal teams are watching closely. In fact, a recent filing within the federal multidistrict litigation (MDL) indicates a renewed effort to revisit the allocation of common benefit fees. For reference, Judge Chhabria famously remarked that the original 8.25% share of the $10 billion settlement fund was “enough to buy a small island” (citations to relevant filings and commentary to follow).

the somatic mutation theory (SMT) remains the predominant scientific framework for understanding carcinogenesis. It is supported by decades of molecular, genetic, and epidemiological evidence demonstrating that the accumulation of somatic mutations in oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes drives the initiation and progression of most cancers.

Landmark studies have shown consistent patterns of driver mutations across tumor types, including mutations in genes such as TP53, KRAS, and PIK3CA, which have been functionally validated in both in vitro and in vivo models of tumorigenesis (Vogelstein et al., 2013; Hanahan & Weinberg, 2011). High-throughput sequencing of tumor genomes has revealed mutational signatures linked to specific environmental exposures and cellular processes (Alexandrov et al., 2013), further reinforcing the causal role of mutations in cancer development.

Hanahan, D., & Weinberg, R. A. (2011). Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell, 144(5), 646–674. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013

Vogelstein, B., Papadopoulos, N., Velculescu, V. E., Zhou, S., Diaz Jr, L. A., & Kinzler, K. W. (2013). Cancer genome landscapes. Science, 339(6127), 1546–1558. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1235122

Alexandrov, L. B., Nik-Zainal, S., Wedge, D. C., Aparicio, S. A., Behjati, S., et al. (2013). Signatures of mutational processes in human cancer. Nature, 500(7463), 415–421. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature12477

Latin for ‘on the threshold’

Share this post