Supreme Court Conference Today

Today marks a significant moment for Bayer, glyphosate litigation, and broader pesticide regulation. The U.S. Supreme Court is considering Monsanto Company v. John L. Durnell (No. 24-1068), the third petition of its kind following Hardeman (No. (21-241) and Pilliod (No. (21-1272), both of which were previously denied certiorari. The outcome could have major implications for the future of preemption and product liability in the context of EPA-approved pesticide labeling, and much more.

Supreme Court conferences are private, confidential meetings attended exclusively by the nine Justices. These gatherings occur regularly during the Court’s term and particularly after long recesses. The conferences serve two primary purposes: deciding which petitions for certiorari (requests to hear a case) to grant, and determining the outcomes of cases already argued.

Under the “Rule of Four,” at least four Justices must agree to accept a case for review. During conference discussions, the Chief Justice speaks first, followed by the other Justices in order of seniority, with no interruptions allowed. Votes are cast in this setting, and once a decision is reached, the most senior Justice in the majority assigns the opinion writing. These discussions are strictly off-the-record—no clerks or outsiders attend, and no notes leave the room—preserving the Court’s longstanding traditions of trust, decorum, and secrecy.

Currently, the Court is considering a significant and increasingly contentious question that highlights the growing divide between federal and state courts on a critical regulatory issue in pesticide litigation: Does the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA) preempt state-law failure-to-warn claims when the EPA has expressly declined to require such warnings?

Federal vs. State Court Disagreement

At the heart of the issue is whether plaintiffs can use state tort law to impose warning requirements on pesticide labels that go beyond what the EPA mandates or permits.

Federal Courts: A Deepening Circuit Split

The Ninth and Eleventh Circuits hold that FIFRA does not preempt state-law failure-to-warn claims—even when the EPA has repeatedly rejected those warnings. Key cases include Hardeman v. Monsanto Co. and Carson v. Monsanto Co.

The Third Circuit sees it differently. In Schaffner v. Monsanto Corp., it ruled that FIFRA does preempt such claims, framing any deviation from federally approved labels as impermissible.

State Courts: Fragmentation Continues

State courts mirror this divide, often within the same geographic regions covered by split federal circuits.

A Pennsylvania appellate court sided with the Ninth and Eleventh Circuits in Caranci v. Monsanto Co., rejecting preemption. This means that within the Third Circuit’s territory, outcomes vary based solely on whether a case is filed in state or federal court.

In Missouri, the Court of Appeals in Durnell upheld a seven-figure damages award, ruling that the state-law failure-to-warn claim was not preempted by FIFRA. Another Missouri appellate court later affirmed a nine-figure award, relying heavily on Durnell—decisions that would likely be preempted in other jurisdictions.

So, the sitation is fragmented at multiple legal levels.

The Stakes for the Supreme Court

The current legal fragmentation means that the success of product liability claims involving glyphosate can depend heavily on the jurisdiction where the case is filed. This lack of uniformity has created significant uncertainty. Monsanto describes the situation as “intolerable,” emphasizing that:

The Durnell verdict effectively imposes a cancer warning for glyphosate, despite the EPA’s repeated conclusions that such a warning is unwarranted.

Manufacturers cannot simultaneously comply with federal law and conflicting state court rulings that impose additional warnings not approved by the EPA.

As Monsanto seeks Supreme Court review, the stakes extend beyond the company itself. The Court’s decision will shape the delicate balance between federal regulatory authority under FIFRA and the rights of states to impose tort-based requirements through their courts.

Yet, this case involves more complex issues and broader implications than often appreciated.

Why Durnell Matters Far Beyond Glyphosate

The Supreme Court’s potential review of Monsanto Company v. John L. Durnell could have far-reaching consequences that extend well beyond glyphosate or Roundup. At the center of the case is a critical question of federal preemption: whether the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA) bars state-law failure-to-warn claims when the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has repeatedly concluded that additional warnings are unwarranted and cannot be added without prior federal approval.

While the immediate context involves pesticide regulation, the implications stretch to other federally regulated products—particularly those overseen by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), such as pharmaceuticals, medical devices, and food labeling. The legal issue in Durnell mirrors ongoing litigation in these sectors: if federal agency approval of labeling preempts conflicting state requirements, manufacturers may be shielded from a wide range of tort claims. A ruling in favor of broad preemption could significantly reinforce legal protections for companies whose products comply with federal labeling standards, potentially reshaping the landscape of product liability litigation.

Moreover, the case addresses a well-recognized and deepening split among state and federal courts over the scope of FIFRA preemption. Resolving this conflict could harmonize legal standards nationwide, clarifying the extent to which states can impose additional warning obligations on products already regulated under federal law. Given the structural similarities in preemption language across statutes, such a decision could also influence judicial interpretation in cases arising under the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act and other regulatory frameworks.

The economic and agricultural stakes are equally significant. If the Court declines to intervene—or ultimately rules against Monsanto—the resulting liabilities could drive Roundup off the U.S. market. Glyphosate is used on over 300 million acres of American farmland, and its removal could lead to higher production costs, food price volatility, and increased reliance on less efficient or more environmentally burdensome alternatives. However, alternatives to glyphosate do exist, including other herbicides with different modes of action, as well as integrated weed management practices such as crop rotation, mechanical weeding, and cover cropping. While these alternatives may reduce dependence on glyphosate, many come with their own economic and environmental trade-offs that farmers must carefully consider.

The Importance of State-Level Protections?

While federal regulatory agencies like the EPA establish uniform standards based on extensive scientific review, state tort law plays a complementary role as a vital safeguard for individuals who may experience harm despite federal approval. It is important to recognize that aspects of FIFRA related to “registration and defense thereof” mean that claims of manufacturer “immunity” from liability are often overstated or misleading.

Plaintiffs and public health advocates argue that state-level failure-to-warn claims provide an essential mechanism for accountability and consumer protection, especially in situations where federal agencies decline to require warnings that some states—such as California—deem necessary based on emerging or localized scientific evidence.

State protections enable more flexible responses to evolving science, regional differences, and individual circumstances that may not be fully captured by broader federal regulatory decisions. This legal tension reflects a critical balance: between the benefits of national uniformity and the need for states to safeguard their citizens through common law remedies grounded in scientific understanding and public health priorities.

Striving for Clarity and Trust in Science and Regulation

This complex legal interplay underscores the importance of pursuing uniformity in toxicological science and transparent, clear communication regarding risks and regulatory safety standards. Too often, comparisons—such as those between EU and U.S. regulatory approaches—are used divisively to sow distrust, fueling fear, uncertainty, and doubt among the public.

Ultimately, fostering trust in science-based decision-making and ensuring consistent yet adaptable regulatory frameworks should be at the forefront of this discussion.

Conclusion

In short, Durnell is not just about the herbicide glyphosate and Monsanto’s argument is truly a bit myopic. This may be a bellwether for how courts reconcile federal regulatory authority with state tort claims across a broad range of industries.

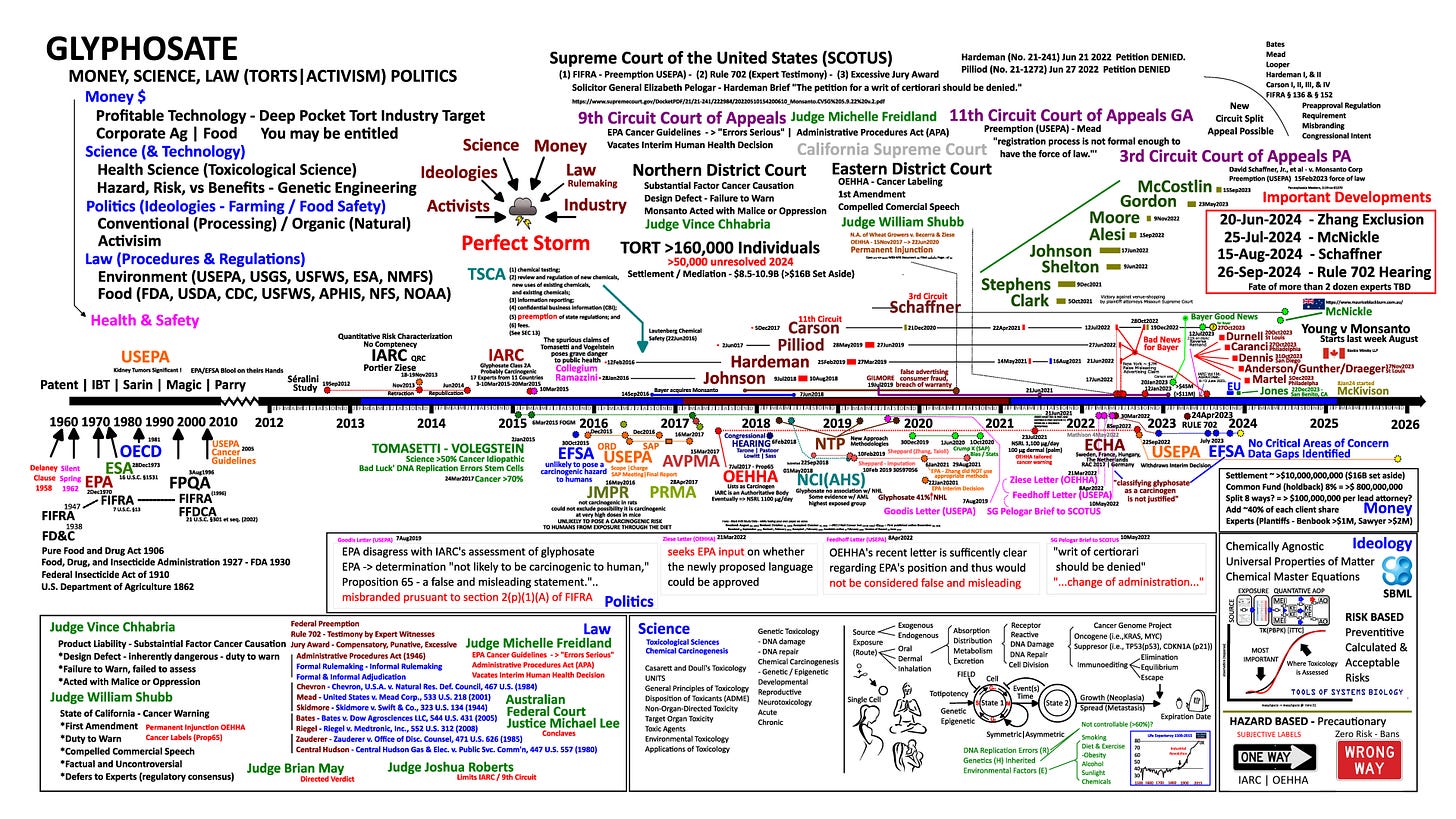

Graphic as last updated September 2024 (it is now far more complex & I’ll strive to update again after SCOTUS publication / decisions that will likely be early next week. All of the above subject to revision. - Edited at 9:10am 26Jun25 - removed ‘crazy’ replacing the ‘So, the sitation is fragmented at multiple legal levels.”

What A.I. thought asking about bias and any misrepresentation of fact.

The Substack post, while informative, leans toward a pro-Monsanto and regulatory authority perspective by emphasizing EPA decisions and portraying state court rulings and plaintiffs’ claims as fragmented or “crazy.” It downplays the scientific and public health concerns motivating additional warnings and frames economic risks mostly from a corporate viewpoint. The language sometimes minimizes the legitimacy of state tort claims and uses informal or subjective terms that could bias readers against those advocating for stronger consumer protections. A more balanced approach would give equal weight to both federal and state perspectives, clarify the scientific controversies, and use neutral language to better reflect the complexity of the legal and health issues involved.

My Response (refined and authentic)

Yes, I called the situation "crazy"—because from a regulatory and legal coherence standpoint, it is. That word reflects my reaction to years of watching inconsistent state-level rulings collide with a decades-long federal scientific review process. I understand how any defense of regulatory science, especially regarding glyphosate, can read as “pro-Monsanto,” but that’s not my intent. My perspective is rooted in the need for evidence-based policy and regulatory clarity.

I did make a point to acknowledge the legitimacy of state tort law, and I’m open to refining that further if it came across as dismissive. I’ll always argue that trust in science is built on transparency, reproducibility, and openness—and that principle applies to both the EPA and to those raising concerns. What I’m not doing is pretending that every court ruling automatically reflects scientific consensus or that every label warning is inherently protective.

No single post can unpack all the glyphosate science, nor should it try. But I’ve followed it closely for a decade, and this post reflects my read of a moment where law and science are in tension—and why that matters.

I’ll remove ‘crazy’ - in the post and consider other perspectives.